No Way Out, No Way Back

A 1997 concert memory, a framework for living with “problematic artists,” and what Sean Combs: The Reckoning forced me to admit about power, nostalgia, and what I’m no longer willing to carry.

This essay discusses sexual misconduct allegations and coercive behavior as portrayed in Sean Combs: The Reckoning.

Act I

No Way Out (1997)

The first feeling wasn’t excitement. It was disbelief.

Disbelief that my mother had been paying close enough attention to know how badly I wanted to see that show. Disbelief that she’d noticed the way I obsessed: learning lyrics, replaying songs in my bedroom, living inside music with the Discman and boombox she bought me years earlier. I felt honored, not because of the tickets, but because she had seen me.

I still remember how she did it. She waved an envelope and crooked her finger toward me. When I leaned into the car, the tickets were spread out. Three of them. One for her, one for my older sister, and one for me.

It was late November, already dark. That detail matters because I understand now what the effort looked like. After teaching all day as a public school teacher in Richmond, my mom went to buy the tickets first, wherever you bought concert tickets in 1997, probably somewhere in the city near her school. I don’t even know exactly where. I never asked. As a kid, I assumed tickets just appeared.

Only after that did she drive past our house and continue to our church, where the Christmas play rehearsal was already underway.

That wasn’t a casual errand. That was intention stacked on effort.

She was smug about it too, in the best way. On the ride home from rehearsal, the play she wrote and directed for our children’s ministry, she kept asking me, “Did you have any idea?” Like she was savoring the reveal.

I was 13 and hyper-aware that I was about to turn 14. My parents were protective, but something had shifted that year. My older sister had left for college, and my mom looked up and realized I was the only child still at home. Tall, confident, tuned in, hungry for culture. With my dad working nights, it became our first real stretch without the usual buffer in the family dynamic. We butted heads constantly, but alongside that friction was something else: my mother paying close attention, studying my interests, choosing to meet me where my joy was evolving.

We lived in a small, rural Virginia county. It moved more slowly than the world on TV. But we had cable. We had MTV, VH1, and BET. We had the early versions of the internet, even if it was slow, loud, and tied up the phone line. And even in a place that felt far from the center of anything, Bad Boy reached us. Puff Daddy. Ma$e. Lil’ Kim. 112. The Black kids knew. Plenty of white kids knew too. That was the point. It was massive, and it arrived anyway.

That night mattered because it was bigger than a concert. It was my mother co-signing my cultural life. It was my family spending money we did not have to create a memory we could keep.

By 1997, Puff Daddy was more than a hitmaker. Yes, he was connected to Jodeci and Mary J. Blige early in the decade, and that alone would have been enough. But by the mid-to-late ’90s, the Biggie era, the Ma$e and Lil’ Kim moment, the R&B groups, it all made him feel omni-genre. He seemed to love Black culture and also knew how to package it as something glossy, expensive, and mainstream. To me, Puffy’s taste and timing felt like an update button for music.

Black adults around me liked him. They saw youth culture with polish. People talked about his dancing, like refinement still mattered. Even those who didn’t know his New York history understood the image.

And I was immersed. Video Vibrations. Rap City. Midnight Love. Teen Summit. The media treated him like a musician even though he wasn’t one in the traditional sense. He commodified curating vibes. Even as a kid, I could feel that power.

That night at the Richmond Coliseum felt like entering a world. Avirex everywhere. The bass was so heavy it felt like weather. A room full of people who knew every word.

My mom wasn’t afraid. That mattered too. She worked in the city every day, then brought us home to a county where race and belonging were never neutral. She had already lived the crossing between worlds, and she carried that steadiness into the arena. I hadn’t. I remember being nervous in ways I can name more clearly now.

But we were fine. We were together. And in that room, I learned something that never left me. Taste has power. What I loved was not private. It was shared. It was scalable. It had an audience.

My mom and sister also taught me lineage. They told me songs were samples. One night, driving home from the mall, one of them showed me that “The Message” was the root of what I was singing along to when “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down” came out.

Looking back, I see the music nerd I still am. I remember being fascinated by how performers sounded live versus on record. I remember realizing, for the first time, that rap was craft.

Puff Daddy was the visual, vocal, and media architect of my most formative music era. Coming into your cool with Bad Boy at its peak leaves a mark you don’t erase by clicking “don’t play this artist.”

That’s not how memory works.

Interlude

The System I Was Always Building

I didn’t wake up one day and decide to build a system for evaluating artists. I was trained in it.

When you are a gay kid who has a hard time passing for straight, you learn early how to hold two realities at once. You listen closely to what is said in public, then compare it to what happens behind closed doors. Every Sunday in church, I heard judgment passed on homosexuality. Then I watched adults stand up and “testify,” crying and confessing behaviors that looked less like purity and more like obsession, addiction, or shame.

As I got older, the pattern clarified. Some of the pillars and leaders in my life were also people living secret lives. That contradiction didn’t confuse me. It taught me how humans work.

I applied that same lens to art.

Even as a kid, certain stories stuck with me, like rumors of R. Kelly’s marriage to Aaliyah. The old legends we were told about rock stars. The way my mother could love Elvis movies and still remember how young Priscilla was when they met. These weren’t presented as scandals. They were facts you carried alongside the work.

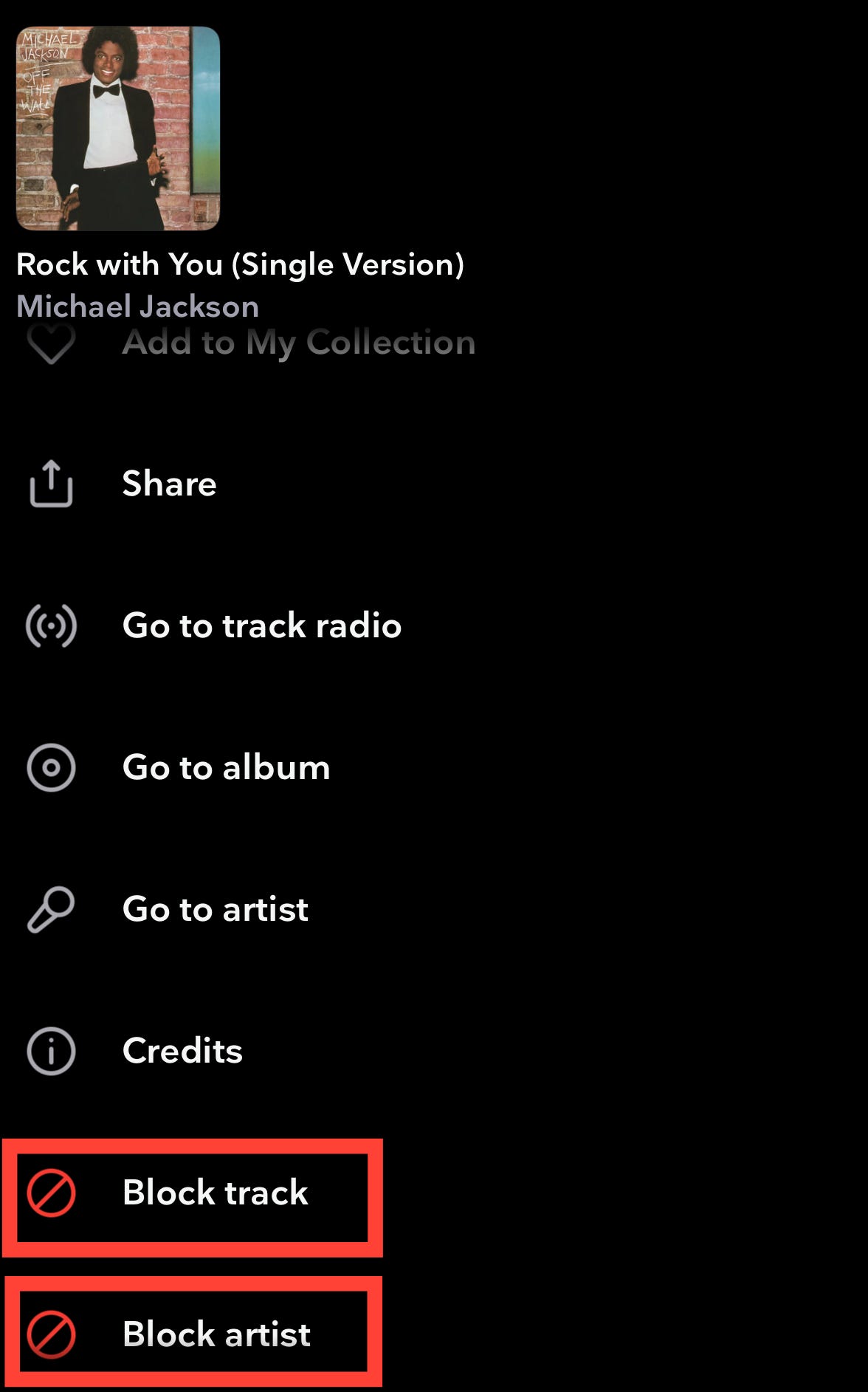

By adulthood, the reckoning became unavoidable. Watching Leaving Neverland with my partner was a turning point. We couldn’t keep listening to Michael Jackson without hearing the lyrics differently. So I made a decision that felt enormous. I asked my streaming platforms to stop recommending him. I’d already done the same with R. Kelly. The art had collapsed too closely into the harm.

What people miss is that I never stopped cataloging.

As a kid, I was bored, so my mother told me to expand my vocabulary or learn a new skill. I chose words. I’d pick one from the dictionary and use it relentlessly, then watch how people reacted and who they assumed I was. By ten or eleven, I wasn’t “hyper” anymore. I was “a gifted writer.” I learned early that forming a point of view and articulating it was my currency.

That instinct followed me into adulthood. By 21, as a history major and part-time park ranger leading public tours of Richmond during the Civil War, I spent my days explaining morally indefensible choices by historical figures. Cataloging wasn’t an endorsement. It was a responsibility.

That’s still how I move through art. Cataloging means consuming the person, the work, the moment, and then deciding where it lands personally, culturally, and historically.

I don’t erase art that shaped me, and I don’t excuse the people who made it. I document the truth of both and decide what I can live with going forward.

That system worked.

Until it didn’t.

Years later, I found language for this tension in Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma. Not because it handed me a clean answer, but because it treated the question with the seriousness it deserves: what do we do with art that shaped us when the person behind it is morally compromised?

That framing didn’t change my values. It sharpened my practice. It gave me permission to stop chasing purity and start naming reality: love for the work can coexist with clarity about harm. If you’ve ever felt your stomach drop while a “classic” plays, Monsters is worth your time.

Act II

The Reckoning (2025)

Act II.1 — The System Fails

I thought I had a system. I was wrong.

Or maybe that’s not quite right. The system itself didn’t fail. It was overwhelmed, stress-tested by scale, by proximity, by the way the past sometimes stops behaving like history and starts acting like the present.

I told myself I was prepared. I had lived through enough reckonings to believe I knew what they felt like. I had already removed artists from my daily rotation. I had already practiced the muscle of separation.

So when the four-part Netflix documentary Sean Combs: The Reckoning arrived, I approached it the way I approach most things now: deliberately, with distance, with my cataloging instincts fully intact. I thought I was watching to understand, not to feel.

That assumption lasted about one episode.

What I wasn’t prepared for was how physical the experience would be. How quickly analysis gave way to activation. I remember standing on my bed with my shoes still on, like my body didn’t trust the floor beneath me. That’s not a metaphor. That’s memory.

I wasn’t just absorbing information. I was reacting to exposure.

What unsettled me more than the allegations was the footage: the intimacy of it, the timing of it, the sense that we were watching a man document himself in proximity to collapse. I kept asking the same question: why does this exist?

Cataloging assumes distance. This documentary collapsed it.

Act II.2 — What the Documentary Shows and What It Doesn’t

The series doesn’t begin with innocence.

By the end of the first episode, viewers learn about a celebrity-sponsored basketball game on a college campus, promoted by Heavy D and Sean Combs, where overcrowding led to the deaths of nine people. The series frames it as an early marker of recklessness. For anyone too young to remember that era of New York news, it reframes the origin story. Puffy’s career emerges not just from ambition, but from proximity to catastrophe and a long history of partial accountability.

The series spans four episodes and traces the rise of Bad Boy Records alongside its consequences. It begins with Sean Combs' firing from Uptown Records and follows the cultural explosion that followed Biggie's death. The narrative delves into the layering of violence, abuse, and control across an industry where intimidation and silence were treated as usual, while also highlighting hilarious anecdotes of Combs’ mediocre, if not talentless, music attempts. Finally, it examines how the public reacted to the court case that unfolded in 2025. The central theme is not about a single event; rather, it is about the accumulation of experiences and incidents.

The documentary includes public statements from former collaborators, employees, and artists. They describe fear, manipulation, and silence as a condition of proximity to power.

And still, omission tells its own story.

Many Bad Boy or Combs fans are aware that he has a sister. One aspect of the documentary that frustrated me was how each speaker depicted Combs' childhood as if he were an only child. Throughout the film, I kept wondering how his sibling might be represented and whether Sean’s mother created a similar environment for both of her children. Since my sister plays an integral role in all of my stories and personal development, I found it particularly bothersome that this detail was overlooked more than it should have been.

The infamous White Parties, attended by hundreds of high-profile figures, remain largely unexamined, just as they did in the courtroom. I thought about how power and influence determine what is interrogated and what remains untouched.

Curtis Jackson, also known as 50 Cent, is a public adversary of Sean Combs, also known as P. Diddy. He has released diss tracks targeting Diddy, and one of 50 Cent's former partners recently became Puff Daddy's public girlfriend, who testified during this summer's trial. The funder and distributor of the most impactful documentary I have seen in the last 3-5 years is actually 50 Cent's most prominent opponent, which leaves me feeling a bit bewildered. At times, I was tempted to stop watching the documentary after considering 50 Cent's involvement in its production.

It also matters who’s telling the story. The series is directed by Alexandria Stapleton, whose documentary work has repeatedly focused on power, identity, and systems. You can feel that background here. The Reckoning is less interested in a salacious recap than in accumulation, patterns over time, and how people rationalize what they already know.

That doesn’t make the documentary neutral. It makes it authored. And the authorship is part of why it lands the way it does.

Act III

What I Keep / What I Refuse

I’m not willing to let this reckoning flatten the entire era into one man’s story.

I keep the aesthetics. I keep what that era did for style and self-presentation, including what it showed about size, swagger, and dignity on a mainstream stage. I keep Sean John as a cultural chapter I want to understand more deeply, because it mattered for men of color and for anyone who moved through the world with style in the late ’90s and early 2000s.

I keep the artists. I will still show up for the people who made the music: 112, Ma$e, Faith Evans, Total, Junior M.A.F.I.A., Lil’ Kim, Danity Kane, Day26. I’ll attend the legacy tours. I’ll honor what their work did for rap, R&B, and for me.

What I refuse is the need to keep centering Puff Daddy as the artist, especially where confession becomes performance. I love Last Train to Paris, by Dirty Money, and the Love Album: Off The Grid was really weird, but listenable. Buuuuut I’m stepping back from that part of the catalog where his voice and myth demand to be centered.

I can honor the era without feeding the myth.

Author’s Note

Why I Wrote This Now

I wrote this now because I realized silence wasn’t neutrality. It was avoidance. The documentary forced me to name what I’m keeping, what I’m releasing, and why the difference matters.